Mapping how schizophrenia changes brains

Living with a mental illness such as schizophrenia is confronting, both for the person who has it and their loved ones.

The behaviour of those who have schizophrenia can be troubling, and can include hearing voices, extreme paranoia about being followed in public, or beliefs that friends and family are conspiring against them. Suffers can experience hallucinations, delusions and disorganised behaviour.

But the disorder also involves substantial impairment to cognitive (thinking) skills that are crucial for occupational and interpersonal functioning, such as memory, attention, learning, decision making and reasoning.

Schizophrenia affects each person individually, making it a challenge to treat. People respond to medication differently, and require varying doses. Finding the right balance can take time, and may mean months and even years of trial and error. But new research is revealing the links between the brain structures of people with schizophrenia and cognitive function, as a step towards more personalised treatments.

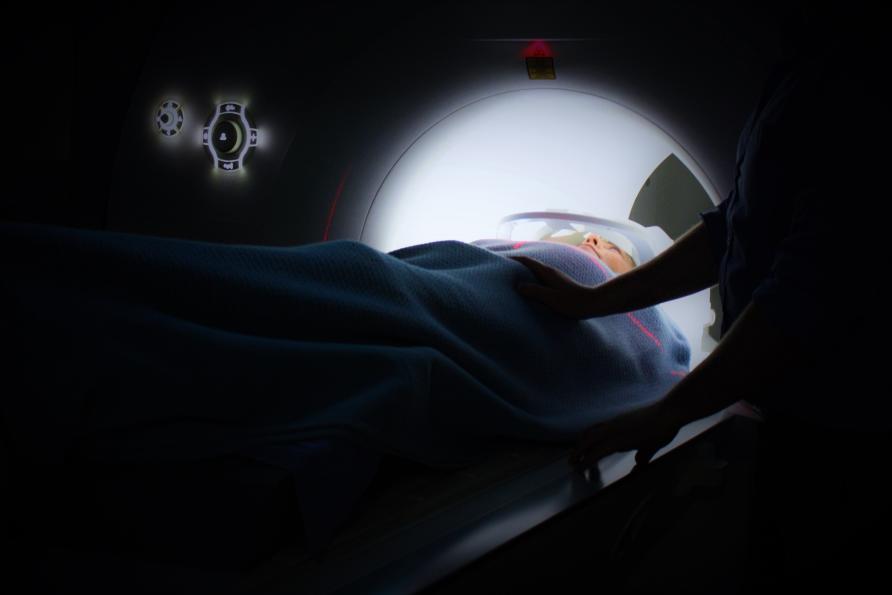

Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans to map the brains of people with schizophrenia, Australian researchers are working to reduce the guess work involved in treating the debilitating illness, and provide new insights that may help to develop better targeted treatments.

The project, led by University of Melbourne researchers, focuses on understanding the brain characteristics of three subgroups of schizophrenia patients. Each sub group had experienced a different impact on their cognitive skills.

- The first group showed average cognitive performance before and since the onset of illness, suggesting a ‘preserved’ cognitive course unlikely to be impacted by neurodevelopmental or neurodegenerative abnormalities. They appeared to be cognitively unaffected by the illness.

- The second group had an average IQ before illness, but poor IQ since, indicating a decline in cognitive functioning. They appeared to have a ‘deteriorated’ cognitive course that probably started with their illness.

- The third group had low IQ before and since illness, and evidence of a ‘compromised’ cognitive course, with abnormalities assumed to originate years before and to continue after the illness manifested.

The study, published in Schizophrenia Bulletin, involves experts at a number of health centres linked to the University of Melbourne, Swinburne University, Monash University and the University of New South Wales.

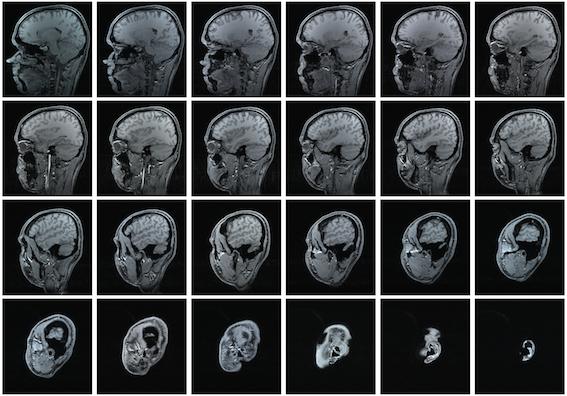

It was the largest neuroimaging study to investigate structural brain abnormalities in the three cognitive subgroups of schizophrenia. Researchers analysed MRI scans to see if the underlying structural brain abnormalities differed between the subgroups, and in comparison to a healthy control group free of psychiatric illness.

With 220 patients and 168 healthy controls, it was larger and more reliable than previous studies.

Schizophrenia patients in all subgroups had smaller brains and a thinner cortex than the control group, but the reductions were most obvious and more widespread in the compromised group.

They included smaller left superior and middle frontal areas, left anterior and inferior temporal areas and right lateral medial and inferior frontal, occipital lobe and superior temporal areas.

Lead researcher and NHMRC Peter Doherty Biomedical Research Fellow, Dr Tamsyn Van Rheenen, says the compromised group did not function cognitively as well as preserved patients. This, coupled with differences in underlying brain structure, suggests the groups have different cognitive profiles and their pathways through the illness may be different.

“Because we saw greater and more widespread brain volume and thickness reductions in the compromised group whose cognitive symptoms are thought to begin earlier, the data backs up the idea that schizophrenia is a progressive neurodevelopmental illness” she says.

Dr Van Rheenen says the results will improve the understanding of cognitive traits in severe psychiatric disorders.

“Our research has provided insight into neural factors that differ between subgroups of people with schizophrenia, which contributes to our understanding of individual differences in the disease course in the disorder,” she says.

“So far, our research suggests that the compromised group has more severe and widespread deficits that could be related to the fact that the cognitive ‘problems’ start earlier in this group than the other groups.”

Dr Van Rheenen says that while the outcomes won’t be direct, a greater understanding of cognition in schizophrenia can help refine the types of interventions and treatments offered and how to target them.

“For example, this research will prompt further studies looking at compromised patients to determine their association to familial or genetic factors that could tell us about how some people may be more ‘at-risk’ for a worse cognitive course of illness than others,” she says.

“This will affect how those people are managed. For example, they may require closer monitoring earlier on, or different types of cognitive treatments.”

Dr Van Rheenen and her colleagues are already recruiting for a new study of neurobiological profiles of cognitive subgroups that she hopes will further improve understanding of individual differences in cognition. They hope that their work will contribute to a move away from the traditional “one size fits all” treatment approach.

“This is the case for most psychiatric disorders,” she says. “Better understandings about individual variation within a psychiatric disorder will help us to tailor treatment approaches.

“This may help to improve diagnosis, and the time it takes for the implementation of an effective intervention because it will eventually reduce the ‘trial and error’ approach often taken.”

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.